Ibn Rušd

Ibn Rušd (Averroes, 1126–1198) has rightly been called the emblematic figure of an “Arabic European” (Thierry Fabre). His commentaries on Aristotle’s works represent a common heritage of the Arabic, Hebrew and Latin traditions of Europe hardly comparable to the work of any other thinker. Born and raised in Córdoba, Spain, to a family of distinguished judges and public servants, he studied law, theology, philosophy and medicine, and became the royal physician (tabib) and the chief judge (qadi) of Córdoba under the Almohad dynasty. His original works and his commentaries on the Corpus Aristotelicum cover almost all branches of classical thought and science, including: Logic, Natural Philosophy, Psychology, Metaphysics, Politics, Ethics, Mathematical-Astronomy, Medicine, Law, Theology, and Grammar. He earned for himself a name as a devoted follower of Aristotle, an excellent and gifted commentator, and widely serves as a symbol for the Andalusian-Peripatetic thought. His impact, though, was much greater on the Latin and Hebrew philosophical traditions than in the Arabic world.

Ibn Rušd (Averroes, 1126–1198) has rightly been called the emblematic figure of an “Arabic European” (Thierry Fabre). His commentaries on Aristotle’s works represent a common heritage of the Arabic, Hebrew and Latin traditions of Europe hardly comparable to the work of any other thinker. Born and raised in Córdoba, Spain, to a family of distinguished judges and public servants, he studied law, theology, philosophy and medicine, and became the royal physician (tabib) and the chief judge (qadi) of Córdoba under the Almohad dynasty. His original works and his commentaries on the Corpus Aristotelicum cover almost all branches of classical thought and science, including: Logic, Natural Philosophy, Psychology, Metaphysics, Politics, Ethics, Mathematical-Astronomy, Medicine, Law, Theology, and Grammar. He earned for himself a name as a devoted follower of Aristotle, an excellent and gifted commentator, and widely serves as a symbol for the Andalusian-Peripatetic thought. His impact, though, was much greater on the Latin and Hebrew philosophical traditions than in the Arabic world.

Córdoba & the Andalusian Golden Age

When Ibn Rušd was young Córdoba already knew some major crisis and suffered from decay, but its intellectual heritage was still alive. The city that once was the thriving intellectual-economical center of Andalusia is indeed a fine example for the celebrated Andalusian “Golden Age.” Merchants and scholars, libraries, public schools and a famous University, outstanding city garden and many public baths – Córdoba was truly a bustling metropolis. The many local scholars had benefit from Córdoba’s famous city library, which once held more than 400,000 volumes! One might try to imagine the long convoys of camels walking in the desert carrying books and transmitting the Greco-Arabic sciences from the East into Western Europe, from Bagdad to Córdoba. The great philosopher Ibn Tufail (1105-1185) lived in the city and introduced Ibn Rušd to the Almohad caliph – Abu Yaqub Yusuf – who later (according to the legend) will ask Ibn Rušd to write commentaries on Aristotle. Between the 10th to the middle of the 11th century the Jewish and Christians minorities enjoyed relatively religious autonomy, a period that ended with the rise of the Almohad. About a decade after Ibn Rušd was born another great philosopher-legislator-physician was born in the city – Moses Maimonides (1138-1204). Twelfth-century Córdoba thus produced the last two giant philosophers belongs to the Arabic-Aristotelian tradition (Falsafah) – a Muslim and a Jew. Both philosophers were professionally affiliated to palace courts but above all desired to travel in the garden of knowledge and the palace of wisdom (Guide for the Perplexed 3.51).

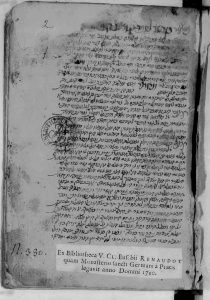

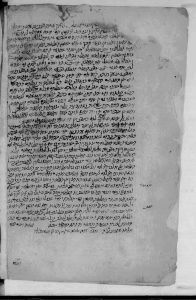

The Translations of Ibn Rušd’s Commentary on Aristotle

For the Andalusian-Peripatetic scholars true philosophy meant Aristotle’s works. From Maimonides’ famous letter to Samuel Ibn Tibbon (Provence), written at the beginning of the 13th century, we can learn about the required philosophical curriculum, i.e. how one should study Aristotle: “Be careful!” ordered Maimonides, since Aristotle’s works, which are “the roots and foundations of all works in the sciences,” cannot be understood “except with the help of commentaries,” those of Alexander, those of Themistius, and those of his Córdoban contemporary Ibn Rušd. The greater the desire for studying Aristotle increased in the Latin and the Hebrew cultures outside Andalusia, so did the need for Ibn Rušd’s commentaries. The necessity to establish new projects that will transmit the Greco-Arabic literature in general and Ibn Rušd’s commentaries in particular was on the rise. This time camels were not needed, but first and foremost dedicated and learned translators. In the Latin West two parallel translation movements grew, Greek into Latin and Arabic into Latin. A few years after Ibn Rušd’s death, in the early 13th century, the systematic translation of his works into Latin and Hebrew was begun and continued until the Renaissance. In the High Middle Ages, the Renaissance, and the centuries thereafter they shaped the reception of the Aristotelian philosophy, and while Aristotle was widely considered as “the Philosopher,” Ibn Rušd was widely referred by his Scholastic and Jewish successors as “the Commentator.” Furthermore, in the Latin and the Hebrew cultures significant “Averroist’’ circlers have developed and the literary genre of the ‘‘super commentaries’’ – i.e. commentaries on Ibn Rushd’s commentaries on Aristotle – has emerged (like Gersonides, Provence 1288-1344).

For the Andalusian-Peripatetic scholars true philosophy meant Aristotle’s works. From Maimonides’ famous letter to Samuel Ibn Tibbon (Provence), written at the beginning of the 13th century, we can learn about the required philosophical curriculum, i.e. how one should study Aristotle: “Be careful!” ordered Maimonides, since Aristotle’s works, which are “the roots and foundations of all works in the sciences,” cannot be understood “except with the help of commentaries,” those of Alexander, those of Themistius, and those of his Córdoban contemporary Ibn Rušd. The greater the desire for studying Aristotle increased in the Latin and the Hebrew cultures outside Andalusia, so did the need for Ibn Rušd’s commentaries. The necessity to establish new projects that will transmit the Greco-Arabic literature in general and Ibn Rušd’s commentaries in particular was on the rise. This time camels were not needed, but first and foremost dedicated and learned translators. In the Latin West two parallel translation movements grew, Greek into Latin and Arabic into Latin. A few years after Ibn Rušd’s death, in the early 13th century, the systematic translation of his works into Latin and Hebrew was begun and continued until the Renaissance. In the High Middle Ages, the Renaissance, and the centuries thereafter they shaped the reception of the Aristotelian philosophy, and while Aristotle was widely considered as “the Philosopher,” Ibn Rušd was widely referred by his Scholastic and Jewish successors as “the Commentator.” Furthermore, in the Latin and the Hebrew cultures significant “Averroist’’ circlers have developed and the literary genre of the ‘‘super commentaries’’ – i.e. commentaries on Ibn Rushd’s commentaries on Aristotle – has emerged (like Gersonides, Provence 1288-1344).

Aristotle’s Physics and Ibn Rušd

Aristotelian Physics has justifiably been called the “Grundbuch der abendländischen Philosophie” (Heidegger). It shaped the scientific approach to nature and set its basic notions, principles and methods for about two thousand years. Aristotle’s Physics determined the view of the cosmos and had also a tremendous impact on medieval theology. Following Aristotle’s definition of Nature as an inner principle of change (Physics II.1), and of Epistêmê as knowledge of causes (Posterior Analytics), Ibn Rušd described the aim of Natural Philosophy as (a) knowledge of the common causes (material, formal, efficient, and final; Physics II.3, Metaphysics V.2) of all natural things, i.e. all things that have within themselves the principle of motion and change; (b) knowledge of the first causes like prime matter and the first mover. Ibn Rušd commentary on Aristotle’s Natural Philosophy includes: commentaries on De Caelo; commentaries on De Generatione et Corruptione; commentaries on the Meteorology; commentary on De Animalibus, and off course commentaries on the Physics. These commentaries have shaped the reception of Aristotle’s Natural Philosophy in the west. Ibn Rušd wrote three commentaries on Aristotle’s Physics: Epitome, Middle and very Long. Only the Epitome has survived in the Original Arabic, while the Middle and the Long commentaries exist in Latin and Hebrew translations alone.

Ibn Rušd admiration for Aristotle is clear. He declare that Aristotle has completed the sciences (logic, Physics, and metaphysics) and that ‘‘no one who has come after him to this our time – and this is close to fifteen-hundred years later – has been able to add a word worthy of attention to what he said’’ (Long Commentary on Aristotle’s Physics). But a close examination of the texts indicates that Ibn Rušd’s commentaries are far from being just simple or faithful interpretations. To what degree did Ibn Rušd himself understood his commentaries as modifying Aristotle’s ideas? and to what directions?

Physics, Spirituality and Virtues

From Plato and Aristotle to Spinoza the idea of philosophical contemplation was never taken as mere professional assignment but firstly as a way of life and a form of being in the world. In the prooemium to his Long Commentary on Aristotle’s Physics, Ibn Rušd argues that the students of the natural sciences will necessarily become distinguished in all the kinds of human virtues: just, truth, humility, generosity, and etc.

“when the scholar knows the scantiness of his life in relation to this eternal existence and to the continuous motion [of the heavens], and that the relation of his life to eternal time is as that of a point to the line, and in general, as that of the smallest finite to the infinite, he will not be overly devoted to life and will necessarily be courageous” (trans. by S. Harvey).

Following the Socratic paradigm of philosophical contemplation, natural philosophy will liberate one’s soul from the fear of death and will strength him with virtues and perfection. Relaying on Alexander’s lost commentary on the Physics, Ibn Rušd presents the ideal of imitating nature: “The students of the physics must be just because when they know the nature of justice which exists in the substance of the beings, they will want to liken themselves and acquire the same form”. The true inquiry of nature through the study of Aristotle’s Physics should be understood as a spiritual and moral act. The student, Ibn Rušd continues, “will become temperate, clinging to the divine laws and following the natural nomi.” The study of nature can constitute perfect individuals and excellent society.

Ibn Rušd & the Western Civilization

If one sees the idea of Europe as a society based on scientific rationality, grounded in the Greek discovery of philosophy as a “new attitude” towards the world (Husserl), Ibn Rušd’s Aristotle commentaries must be understood as one of the most important elements of linkage in the intellectual history of Europe. The transmission and reception of Ibn Rušd’s works, and their cross-cultural heritage, represents what Europe and the Western Civilization can be in its best – a common pursuit for knowledge and better understanding of its own origins in their highest form.